World War I

United States Involvement: 1917 – 1918

When war broke out in Europe in the summer of 1914, few Americans–if any–believed the United States would ever have a direct role to play in the conflict. Although the U.S. had participated actively in the international naval arms race since the 1880s and had seen fit on numerous occasions in recent years to employ its military resources as an instrument of national policy, the causes of the European war seemed remote and incomprehensible. Thus, it may have appeared sensible for President Woodrow Wilson to order the nation to remain neutral in spirit as well as deed–a condition that lasted only a short time as Americans began to favor one side or the other, whether for the sake of business or personal reasons.

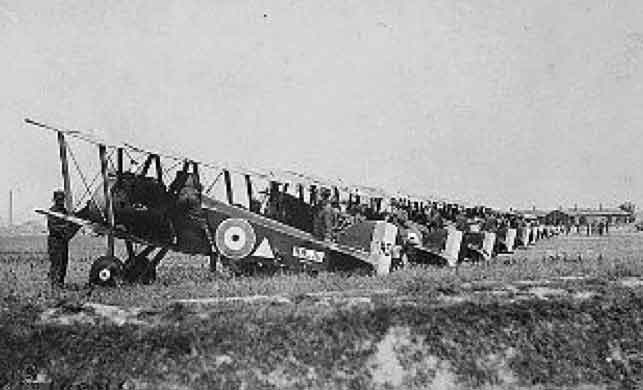

The war between the Triple Entente (Imperial Russia, France and Great Britain) and the Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy) unfolded on a main eastern and western front as well as along several smaller ones, and soon ground down into an immensely destructive stalemate all around. Thanks to recent advancements in military technology, including “magazine-loading rifles, belt-fed machine guns, and improved artillery,” to say nothing of effective submarine warfare and military aviation, the Great War as it was called at the time proved more destructive to life, limb and property than anyone had imagined.

The dynamic American economy benefited from a lively trade with the belligerents, but the nation’s military assets seemed far too small and distant from the conflict to be of any particular use (in 1916, the U.S. Army ranked 17th in the world and the Navy still had far to go before it could claim a status “second to none”). Nevertheless, President Wilson had been eager since early in the war to serve as an impartial mediator to bring the conflict to a definitive end, and he came to the realization as the war dragged on that American participation in the combat would be his only sure entrée to peace negotiations. American neutrality had become a legal fiction as the U.S. had allowed the Allies–Britain and France in particular–to become increasingly dependent credit and supplies of goods from the United States. Political sentiment remained sharply divided over the war, with some of the country’s top leaders preaching antimilitarism and non-intervention while others believed it was high time for the U.S. to become directly involved.

According to David Woodward in The Oxford Companion to American Military History:

Caught between the effective Allied naval blockade and Germany’s submarine warfare campaign, America’s right to overseas trade was jeopardized…. Wilson’s mediation efforts implied that he was prepared to accept a global role for the United States to obtain a compromise peace, but he certainly never imagined any circumstances that would involve American forces in what he referred to as “the mechanical game of slaughter” in France. Nor apparently could he identify any strategic interest for the total defeat of Germany….His formula for a satisfactory end to the fighting as he announced in January 1917 was “peace without victory.”

In response to Wilson’s request, Congress declared war on the Central Powers in April 1917. Not since the War for Independence had the U.S. joined with another country as part of a military alliance. Although the General Staff of the War Department thought American forces should join in a collective military enterprise with the British and French on the western front, American combatants served as an “associate power” with freedom to conduct independent goals. Public opinion remained as sharply divided after the declaration as it had been before, so the Wilson administration worked hard to squelch dissent and convince Americans to pull together for the sake of the war effort, ultimately promoting “a frenzy of anti-German and anti-German American feelings in parts of the nation.”

Thanks to a flurry of legislation the economy all but entirely converted to a war footing and society in general mobilized to an extraordinary extent. The federal government took control production, procurement and distribution of most goods, giving those companies that chose to cooperate with the largely voluntary system opportunities to earn enormous profits. The Selective Service Act of 1917 established a system of conscription run mainly by volunteers working in more than 4,000 local draft boards across the country. Before war’s end, the Selective Service System registered 23.9 million men, and drafted 2.8 million of them into an army that totaled 3.5 million soldiers.

In command of the American Expeditionary Force was General John J. Pershing, lately returned from the unsuccessful Punitive Expedition in Mexico. Pershing was able to preserve the independence of his army, complete “with its own front, supply lines, and strategic goals.” Entering combat under the American flag in May and June of 1918, the AEF proved effective in offensive as well as defensive operations in the Allied cause: “Although only involved in heavy fighting for 110 days, the AEF made vital contributions to Germany’s defeat. With tens of thousands of ‘doughboys’ crossing the Atlantic to reinforce the Allies, and with the AEF emerging as a superior fighting force, the exhausted and depleted Germans had no hope of avoiding total defeat if the war continued into 1919.”

By the time the Allies accepted Germany’s call for an armistice on November 11, 1918, more than 65 million troops had been mobilized for the Great War. Millions of British, French, Russian and German troops were sacrificed to a cause that even today is not well understood. Rather than the permanent peace that should have provided a fitting legacy to the “war to end all wars,” Woodrow Wilson’s ambitious and idealistic plan to shape the postwar world yielded a deeply flawed peace that lasted less than twenty years before the world was engulfed by war once again.

RECOMMENDED READING

Pershing: General of the Armies

by Donald Smythe

The Doughboys; the Story of the AEF, 1917-1918

by Laurence Stallings

Yanks: the Epic Story of the American Army in WWI

by John S. D. Eisenhower

Final Report of General John J. Pershing, Commander in Chief, American Expeditionary Forces

by John J. Pershing

All books are available at our Museum Library which is open to the public every Thursday from 10am to 4pm.

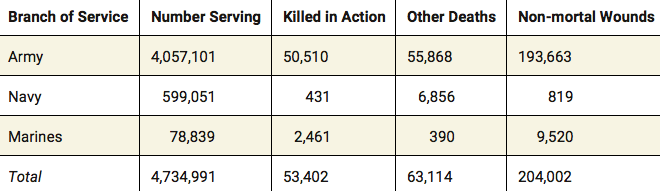

AMERICAN CASUALTIES