Vietnam War

1964 – 1973

Beginning with modest steps as early as May 1950, when President Truman provided military and economic aid to the French effort to retain their colonial control of Indochina, the United States became increasingly involved in a difficult, distant war that did not end until 1973. The French were defeated in 1954 by the Vietnamese Nationalist Army–the Communist-led Vietminh. At a peace conference later that year in Geneva, Ho Chi Minh obliged France to allow him to establish Communist control north of the 17th parallel while a non-Communist government would rule south of that line. According to the agreement that emerged from the conference, countrywide elections were to follow in two years’ time whereby all the people of Vietnam would either unite under Ho Chi Minh’s government or leave the country permanently divided. The United States, a participant in the peace conference, never accepted its outcome, and acted in concert with the government of the south to prevent the election from ever taking place. President Eisenhower himself acknowledged that, had the Vietnamese people been allowed to express themselves at the polls under the terms of the agreement, “‘Ho Chi Minh would have won 80 percent of the vote’–and no U.S. president wanted to lose a country to communism.”

The Eisenhower administration decided to create a nation of South Vietnam “by fabricating a government there, taking over control from the French, dispatching as many as 740 military advisers to train a South Vietnamese army, and unleashing the Central Intelligence Agency to conduct psychological warfare against the North.” Cognizant of the Allied experience in World War II as well as the costly but inconclusive outcome of the war in Korea, Eisenhower was unwilling to commit the United States to a land war in Southeast Asia. Under the leadership of John F. Kennedy, however, the U.S. began to commit more and more American military assets to South Vietnam, for three apparent reasons: first, to fulfill the promise dating from the Eisenhower years that the U.S. would never abandon its South Vietnamese allies, who were by then fighting a widespread guerrilla war against Communist-led troops of the National Liberation Front (NLF, also known as Vietcong) of South Vietnam; second, to fight what American policymakers characterized as the spreading cancer of Communism; and third, to prove the strength of his “resolve to the American people and his Communist adversaries”–issues adopted by Lyndon Johnson as his own in the wake of Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963. By the time Johnson inherited the situation in Vietnam, more than 16,000 U.S. military advisers were “in country,” the first wave of 400 having been sent there secretly by Kennedy in 1961. As of November 1963, more than one hundred American soldiers had died there. The American advisers’ most important mission was to enable the army and government of South Vietnam to defend itself against the increasingly effective onslaughts of the Vietcong. When two U.S. Navy destroyers–Maddox and Turner Joy–reported alleged attacks by North Vietnamese gunboats in the Gulf of Tonkin in August 1964, the Johnson administration presented a previously prepared resolution to Congress that passed almost unanimously, giving the president a “blank check” to conduct the war as he saw fit.

Neither Johnson, his successor to the presidency Richard Nixon, nor the military and diplomatic establishments under their direction proved able to develop strategy or tactics capable of achieving the stated American objectives. Indeed, by the summer of 1964, the situation on the ground in Vietnam appeared overwhelming: the Army of the Republic of [South] Vietnam (ARVN) had shown itself to be incompetent and unwilling to fight; the “strategic hamlets” program established during Kennedy’s administration (“fortified villages…intended to insulate rural Vietnamese from Vietcong intimidation and propaganda”) had failed for a number of reasons; South Vietnam’s Buddhist majority stepped up its protest against what it perceived to be the mainly Catholic government’s religious persecution; North Vietnam’s aid to the Vietcong insurgency had greatly increased; the Vietcong now controlled vast areas of South Vietnam; and the Kennedy administration itself contributed to the turmoil by failing to intervene when ARVN officers murdered President Ngo Dinh Diem and his brother and seized control of the government in Saigon.

Between the time he acceded to the presidency and the Gulf of Tonkin incidents eight months later, Johnson continued most of American policies then in operation, including covert intelligence gathering operations, dissemination of propaganda, and military harassment of North Vietnam. But with the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in hand, and the advice of newly appointed commander General William Westmoreland, Johnson began an inexorable program of escalation.

The first significant advance was Operation ROLLING THUNDER, an aerial bombing campaign over North Vietnam that included more than 212,000 sorties between 1965 and ’67 intended to destroy military bases, supply depots and infiltration routes. American bombers also targeted the Ho Chi Minh Trail where it passed through Laos as well as factories, farms and railroads in North Vietnam. Political instability continued to plague South Vietnam, and the growing American investment in bombs, dollars and advisers failed to prevent the Vietcong from inflicting heavy casualties on the ARVN. Thus, in concert with Westmoreland and his advisers in the Pentagon and White House, Johnson ordered the insertion of Marine and Army units whose job it would be to fight the Vietcong themselves rather than advising the ARVN. Before the end of 1965, more than 184,000 U.S. military personnel were in South Vietnam, a figure that continued to grow until early 1968, at which point American troop levels peaked at approximately 500,000.

In order to limit the risk of a wider war with Ho’s main patrons, China and the Soviet Union, Johnson and Westmoreland held back from any attempt to annihilate North Vietnam, choosing instead to fight a war of attrition in the South. The North Vietnamese responded by sending more of their regular army (NVA), that now engaged in heavy combat with American forces for the first time. While the principal American tactics–“search and destroy” missions, strategic and tactical bombing of enemy positions from the air, and extensive use of helicopters for many different purposes–succeeded in killing large numbers of enemy troops, attrition neither improved the political situation in the South nor deterred NVA and NLF forces from stepping up the fight.

Control of territory proved especially problematic: in numerous instances, having driven the enemy from the battlefield, the air-mobile Americans withdrew themselves. Perhaps just as often, Vietcong guerrillas “disappeared when U.S. forces entered an area, [and] quickly reappeared when the Americans left.” Worse, despite suffering huge losses on the battlefield, the NLF exercised more effective control in many in many areas than did the government of South Vietnam. In fact, when General Westmoreland announced to the American public late in 1967 that he could see “the light at the end of the tunnel”–in other words, that victory was in sight–the war had settled into a military and political stalemate, with American forces suffering ever higher rates of casualties (more than 14,000 combat deaths in 1968 alone–the highest annual figure for the entire war).

In the meantime, popular support for the war had declined drastically at home while anti-war protests became larger, more vocal, and much better organized. The highly equivocal American victory against the Vietcong in the Tet Offensive of January-February ’68 caused tremendous losses for the U.S. and ARVN forces at the same time that it exacerbated the refugee problem and further contributed to political instability in the South. The Johnson administration’s efforts to keep the massive social programs of the Great Society afloat in the face of mounting costs to maintain the war further eroded the nation’s confidence. When Westmoreland and General Earle Wheeler, chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff requested 206,000 additional troops in the Spring of 1968, a special body of presidential advisers (including Dean Acheson and Omar N. Bradley) convinced Johnson to rely on his conclusion that the United States had reached its limit in Vietnam.

Providing manpower for the American war effort proved to be a chronic problem. According to the Oxford Companion to American Military History:

By 1967, almost 50 percent of the enlisted men in the army were draftees. By 1969, draftees comprised over 50 percent of all combat deaths and 88 percent of army infantrymen in Vietnam. No war since the Civil War produced so much opposition to the draft. Part of the problem had to do with its perceived unfairness. Undergraduates, and until 1968, graduate students could defer military service until they completed their programs. In addition, many young men, often from the middle class, joined the National Guard and Reserves on the likely gamble that they would not be called up for duty in Southeast Asia. Consequently, the Vietnam War appeared to many to be a “working class war,” with draftees and enlisted men coming disproportionately from blue-collar backgrounds. At first, from 1965 through 1967, African Americans especially served and died in Vietnam in disproportionate numbers.

In a television broadcast on 31 March 1968, Johnson made three landmark announcements: that he would cut back the bombing of North Vietnam, seek a negotiated settlement with the government of North Vietnam, and that he would neither seek nor accept his party’s nomination for reelection. The new commander in the field, General Creighton Abrams was assigned the task of turning the bulk of the war over to the ARVN–“Vietnamization.” With peace talks as deadlocked as the war itself, Johnson’s successor, Richard Nixon made a show of withdrawing American troops while secretly expanding the war into neutral Laos and Cambodia and re-expanding the bombing of the North that by 1972 included dropping mines into the North Vietnamese harbor at Haiphong. When news of these “incursions” reached the public, anti-war protests surged across the United States and around the world with renewed vigor. In the wake of numerous setbacks and controversies, Nixon’s special envoy to the Paris peace talks, Henry Kissinger, was finally able in January 1973 to conclude an agreement that “allowed the U.S. to leave Vietnam without resolving the issue of the country’s political future.”

The capstone to the nation’s longest and most debilitating war, President Nixon’s “peace with honor,” did not hold for long. Without American troops on the ground or air support, the NVA and NLF managed to capitalize on deteriorating military and political conditions in the South and took control of the entire country by the end of April 1975, at which point “the last remaining Americans abandoned the U.S. embassy in Saigon in a dramatic rooftop evacuation by helicopters.”

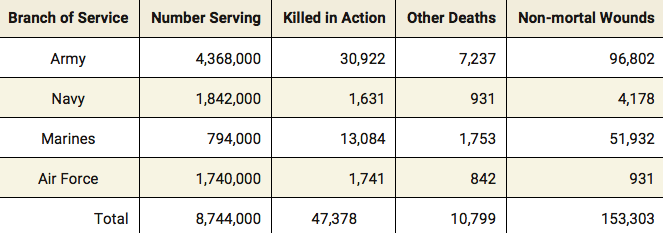

From many different points of view, the costs of the Vietnam War proved to be staggering indeed. The loss of American lives comes to mind first: 58,177, plus approximately 2,500 Americans still counted as “missing in action.” 153,303 Americans sustained non-mortal wounds, while uncounted hundreds of thousands more came home carrying significant psychological damage as well. According the Department of Defense, the direct monetary cost of the war came to $173 billion, to which should be added “potential veterans’ benefits costs of $220 billion and interest of $31 billion.” The myriad indirect costs of the war may defy any final accounting. And we should not forget the enormous loss of Vietnamese lives, whether at the hands of Americans, the ARVN, the NVA or Vietcong-estimated by various sources to be between 1.5 and 3 million.

RECOMMENDED READING

A Better War – The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America’s Last Years in Vietnam

by Lewis Sorley

A Contagion of War

by Terrence Maitland and Peter McInerney

A Nation Divided

by Clark Dougan and Samuel Lipsman

A Soldier Reports

by William C. Westmoreland

All books are available at our Museum Library which is open to the public every Thursday from 10am to 4pm.

AMERICAN CASUALTIES