Spanish-American War

1898

Throughout the 19th century, Americans had been concerned about the Spanish colonial presence on Cuba, just ninety miles off our shores. Although Spain’s power and influence in the world had declined significantly, Americans with business interests in Cuba—primarily sugar planters and processors—worried as the Spanish colonial authorities asserted a program of “reconcentration” on the island that not only seemed to threaten their security, but also brought severe hardships to bear on the Cuban population. Spanish suppression of an indigenous rebel movement on the island was especially harsh after 1895, a fact that William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer went to great lengths to exploit in their newspapers across the United States. President William McKinley and his predecessor Grover Cleveland achieved considerable diplomatic success with the government of Spain, persuading the colonial power to grant near-total autonomy to Cuba and Puerto Rico, although the Cuban insurgents rejected this concession. The sensationalistic “yellow press” sold millions of newspapers with lurid headlines, pictures and reportage describing Spanish atrocities, which had a powerful impact on public opinion in the United States, gradually stirring up a rising tide of war fever, despite strong opposition to war from McKinley and many leaders in Congress.

The U.S. was slow to send the tribute it had promised in 1795 for the purpose of freeing more that one hundred American sailors captured two years before, causing the Pasha of Tripoli to demand payment in terms just short of a declaration of war in 1801. President Thomas Jefferson sent the much diminished U.S. Fleet to the Mediterranean, where in cooperation with ships from Sweden, Sicily, Malta, Portugal and Morocco, they forced the Pasha to back down. From then on, a small naval squadron patrolled the North African coast, until the U.S.S. Philadelphia ran aground in 1803, and the Triplolitans seized the ship and her 300-man crew. Lieutenant Stephen Decatur earned his captain’s bars as well as recognition as a true American hero in 1804 when he entered the harbor at Tripoli, burned the Philadelphia, and bombarded the city. The American consul in Tunis, William Eaton organized a force composed of Arabs, Greeks and U.S. Marines to attack the Tripolitan city of Derne, which they captured just as the U.S. finalized a peace agreement with the Pasha. Decatur returned to the scene once again in 1815 to negotiate a settlement with Algiers, which had declared war on the U.S. in 1807, although no battles were fought due to the fact that the embargo and War of 1812 kept Americans out of the Mediterranean throughout those years.

On the night of February 15, 1898, two tremendous explosions aboard the U.S.S. Maine caused the battleship to sink in Havana Harbor, an event that killed 260 of her crew. The Maine had been dispatched to Cuba three weeks earlier in response to a request from the American consul, who feared for the safety of Americans on the island. Although sailors from Spanish naval ships anchored in the harbor rushed to the aid of their American counterparts, a court of inquiry rushed to the conclusion that Spanish mines had been responsible for the tragedy. (In 1975, a commission under Admiral Hyman Rickover revisited the event, concluding that spontaneous combustion of coal dust in the Maine’s fuel bunkers had caused the explosions.) For the next month, the McKinley administration attempted to avoid citing the sinking as a cause for war and continued to negotiate with Spain for Cuban independence. For reasons of its own, the Spanish government decided that an unsuccessful war with the United States would be a more desirable outcome than giving in at the negotiating table, and so McKinley reluctantly asked Congress for a declaration of war against Spain, which was granted on April 25.

As had been the case throughout much of American history—both previous and to come—the United States was woefully unprepared for war. At the time, the regular army was composed of only 28,000 troops, but between the National Guard and the U.S. Volunteers, an American force was in the field on Cuba late in June; the Navy’s North Atlantic Squadron had established a blockade on the Cuban coast four days prior to the declaration of war. Between 24 June and 17 July, American army forces prevailed in engagements at San Juan Heights near Cuba’s second city, Santiago, and then a brief siege of the city itself, at which point the Spanish capitulated, the six ships of the Spanish navy having already been destroyed.

In the mean-time, the U.S. Navy’s Asiatic Squadron, under the command of Commodore George Dewey, had vanquished a small flotilla of Spanish vessels at Manila bay, the center of Spain’s principal colony in the western Pacific. Unable to communicate with the rest of the world (Dewey had ordered the submarine telegraph cable running between Manila and Hong Kong cut) Dewey had to wait for orders as well as reinforcements to arrive from the United States. Unbeknownst to Dewey, Spain had already capitulated to the U.S., and under the terms of the armistice was supposed to retain possession of the Philippines. But Dewey arranged the notorious “sham battle of Manila” to enable the Spanish colonial authority to surrender with honor, which it did, leaving the Philippines in the hand of the Americans, much to the chagrin of a Filipino nationalist movement under the command of Emilio Aguinaldo. Aguinaldo had been in exile in Hong Kong when Dewey sailed for Manila back in February, and an American naval vessel carried him back to the Philippines after Dewey’s gunners disposed of the Spanish squadron. Aguinaldo operated under the misapprehension that the Americans had liberated his homeland for the sake of Filipino independence, and found himself sorely disappointed when President McKinley and the Congress decided to take formal possession of the archipelago. Aguinaldo’s forces fought against American occupation until their insurgency was finally extinguished in July 1902, and the Philippines remained a part of the United States until 1946.

The Treaty of Paris was signed by representatives from the U.S. and Spain on December 10, 1898. After extensive debate, the treaty was ratified by the U.S. senate on February 6, 1899. Under the treaty, the U.S. acquires control over Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines.

RECOMMENDED READING

A Ship to Remember: the Maine and the Spanish-American War

by Michael Blow

Between the Bullet and the Lie; American Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War

by Cecil Eby

Empire by Default: the Spanish-American War and the Dawn of the American Century

by Ivan Musicant

History of Our War with Spain

by James Rankin Young & J. H. Moore

All books are available at our Museum Library which is open to the public every Thursday from 10am to 4pm.

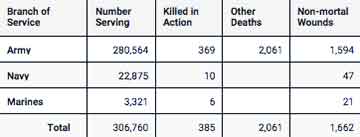

AMERICAN CASUALTIES