Korean Conflict

1950 – 1953

As the war against Japan approached its conclusion in the summer of 1945, the United States and Soviet Union divided the Korean Peninsula, which had been a colony of Japan since 1905, between them into two temporary protectorates. The United Nations proposed free elections across all of Korea in 1948, but the Soviets rejected this plan. An election took place in the American protectorate in the south nevertheless, resulting in the establishment of the Republic of Korea (ROK), while the USSR created the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in the north of the country, and installed Kim Il Sung at the head of its Communist government. U.S troops occupying the ROK were withdrawn in 1949 after the Joint Chiefs of Staff told President Truman that Korea held little strategic interest for the United States. Early the next year, the Soviet Union withdrew its own troops from the North. Kim Il Sung interpreted these events as an opportunity, if not an open invitation, to reunite the two Koreas by force, to which end his armies invaded the South in late June 1950.

Following the government of North Korea’s rejection of a UN resolution that it cease hostilities and withdraw from the South, the UN Security Council appointed President Truman as its executive agent to apply military force to eject the North Koreans from the South under the authority of the United Nations Command. Truman in turn named General Douglas MacArthur as commander in chief of the UN forces. MacArthur was faced with a daunting task: to build a coalition army that could defeat the North Koreans, thus saving the ROK, while confining the violence to the Korean Peninsula and keeping the Soviet Union and China out of the war. American combat units were undermanned, ill-equipped and poorly trained for the circumstances they suddenly had to face.

Fortunately, the nations of the British Commonwealth, along with numerous other UN members (fifty-three in all) made major contributions to the effort early on while the U.S. Eighth Army as well as American naval, air force, and marine units built up their presence.

MacArthur’s troops were able to slow the North Korean advance and then pull back behind the Pusan perimeter in the far south while awaiting reinforcements and preparing to stage an amphibious invasion at Inchon, the capture of which MacArthur believed would force surrender by the Communists. The successful amphibious operation at Inchon caused the communists to retreat from Seoul, while the Eighth Army was able to break out from Pusan and join up with other UN forces to push the Communists back over the 38th parallel, the line dividing the two Koreas since 1945. These events marked the fulfillment of the UN’s and Truman’s original goals, but Truman had in the meantime changed the national objective from saving South Korea to unifying the peninsula. After the General Assembly of the UN passed a resolution to that effect in October 1950, “MacArthur was free to send forces into North Korea,” capturing the northern capital of Pyongyang and moving throughout much of the North against little or no resistance.

The Chinese government had warned the UN armies not to cross the 38th parallel, but with MacArthur’s incursion into the North, the Chinese decided to intervene, at least in part at the request of Soviet premier Josef Stalin. Soon the Chinese had sent more than 260,000 troops into the conflict. Within weeks the combined Communist armies pushed the UN forces back south below the 38th parallel, retaking Seoul in the process. At this point Truman and his British counterpart Clement Atlee decided to give up their goal of unification in favor of restoring the status quo antebellum, i.e., two Koreas divided at the 38th parallel. With that it became the most important objective of the Eighth Army and its new commander, General Mathew Ridgway to stop its southward retreat, regain possession of Seoul, and move north toward and beyond the 38th parallel.

Railing at the prohibition to take revenge on North Korea for his humiliating defeat, MacArthur went public with his dissatisfaction, earning his dismissal by President Truman in April 1951. With Ridgway now commander in chief, the UN forces fought the Communists back and forth across that line through June 1951 when the two sides agreed upon an agenda to negotiate an end to the war. The peace talks dragged on for two more years while the combat situation became static, “more reminiscent of World War I than anything that had happened since,” replete with “a seemingly endless succession of violent firefights” intended to give one side a bit better leverage over the other in the truce negotiations.

Private First Class Roman Prauty, a gunner with 31st Regimental Combat Team (crouching foreground), with the assistance of his gun crew, fires a 75mm recoilless rifle, near Oetlook-tong, Korea, in support of infantry units directly across the valley.

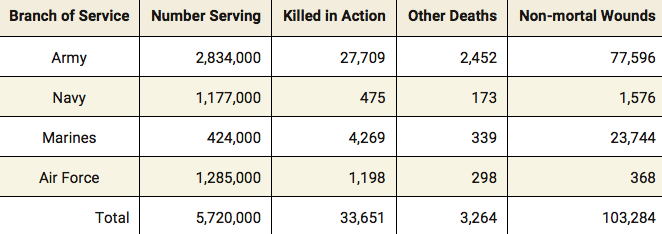

A complex set of events ensued, including the accession of Dwight D. Eisenhower to the presidency, the threat of atomic warfare and the death of Joseph Stalin. Before the armistice, essentially a cease-fire agreement rather than any final settlement to the war, was signed in July 1953, the war claimed between two and three million lives overall. “The UN Command suffered a total of 88,000 killed, of which 23,300 were American. Total casualties for the UN (killed, wounded, missing) were 459,360, 300,000 of whom were South Korean.”

RECOMMENDED READING

Brothers at War: The Unending Conflict in Korea

by Sheila Miyoshi Jager

Chosin: Heroic Ordeal of the Korean War

by Eric Hammel

In Mortal Combat: Korea, 1950-1953

by John Toland

Inchon Landing: MacArthur’s Last Triumph

by Michael Langley

All books are available at our Museum Library which is open to the public every Thursday from 10am to 4pm.

AMERICAN CASUALTIES